SYSK: Strongman, Psychology, Average, Have-a-look and MuchBetter....

Understanding Zimbabwe’s ‘bizarre’ names

I will occasionally share stories and essays about topics of interest to me in this Stories You Should Know section. First up, Zimbabwe’s unusual naming conventions.

Every few months or so, I’ll come across a video on social media about Zimbabweans and their ‘strange’ names. It’s usually titled something like ‘Funniest Zimbabwean names Pt III’ or ‘Crazy names from Zimbabwe’. These clips tend to do well, with a ripe comment section flooded by people sharing the names of cousins and colleagues called BigBoy, Behaviour, Tears, Average, Have-a-look, Doubt, and Computer. As someone born and raised in Zimbabwe, I never paid much attention to these names. I have, after all, a Beer and an Admire in my own family. When a friend was robbed a few years ago, he told me that an Inspector Breakfast was assigned to his case. I joked that only in Zimbabwe could either ‘Inspector’ or ‘Breakfast’ be his name. Perhaps my only double-take was when I came across a document with the name…Clitoris (true story).

Blame it on the algorithm, but these videos have been appearing with greater frequency lately. In the past, I might watch a few seconds to gauge the tone of the video and see who was making it. It tends to be other Africans or Zimbabweans in the diaspora. But recently, something has shifted, and I’ve started to bristle a little at these videos. I suspect it is tied to a broader concern about how information is increasingly served in bite-sized sugary chunks, often stripped of context. I understand that you can’t cram a thesis on the political history of Zimbabwe into a TikTok video. Still, I wish there were more attempts to interrogate this unique naming practice. Why would someone choose to call their child Salad or Welshman? There seems to be no genuine attempt to learn more (Learnmore, incidentally, is another common-ish Zimbabwean name).

Before I provide an abbreviated explanation of this phenomenon, I would like to share a small but important disclaimer: although Zimbabwe has many other ethnic groups, I will focus on the Shona because it is a more common practice among them.

Naming practices are closely tied to the country's political history. In precolonial times, names like Ndaizivei (meaning ‘what did I know?’) or Tanonoka (meaning ‘we are late’) were given to capture the circumstances surrounding the birth or the family’s wider history, ambitions, hopes, and fears for their child.

The period between 1920 and 1950 is perhaps the most illuminating for understanding the genesis of the unusual naming conventions. When the European settlers arrived, they made a concerted effort in convincing locals to adopt English names by associating indigenous names with paganism and backwardness. Official documents, such as birth certificates and school enrollment forms, often included a ‘Christian name’ column. This marked the arrival of names like Peter, James, Ruth, and Miriam. It wasn’t all about overt coercion; part of the success of the colonial project was positioning English and European values as a sign of learnedness.

Alec Pongweni in his excellent paper ‘The impact of English on the naming practices of the Shona people of Zimbabwe’ describes the shift that occurred as these Christian names began to take root:

“Shona parents initially began to give their children Christian names; John, James, and so on. But these were soon found lacking in expressiveness. The culture-bound practice of giving loaded names to children was so much with us that when these Biblical names were found wanting and, concurrently, when the virtue of Western education and some degree of fluency in English became the intellectual Mecca of Shona upward-strivers, English words were picked, unadulterated, from the dictionary, and violently twisted, both semantically and categorically, and used as names for children. The intent remained the same, but the medium of expressing it had changed.”

English became the respectable medium, the way to signal your place in the world, so names that in Shona would communicate the experiences and hopes of a parent, were translated into English. A solid Shona name, such as Kuzivakwashe, became Godknows. Alternatively, a name like Hazvinei, which might have been given as a result of events surrounding the child’s birth, became NoMatter. Many of these ‘strange names’ are English versions that are rarely able to capture the sentiment or intention of their Shona counterpart.

I am not arguing that names like Avoid, Polite, Bottle, or Lesson can simply be chalked down to being ‘lost in translation’, but more often than not, the giver is still applying a storytelling philosophy, even if that story might appear odd to an outsider.

It’s worth noting that another way the Shona people responded to the first missionaries was by converting common English nouns into Shona names, such as Chiedza (Dawn), Rudo (Love), and Nyasha (Mercy). It was a way of threading the needle.

Much has happened in Zimbabwe over the past three decades. There has been a massive economic exodus, and with that has come a new wave of names as people give birth abroad, with some opting for traditional Shona names or ones that reflect their new lives in new countries. At home, however, the trend toward unique names persists. I recently came across a list that purports to be taken from the Registrar of Births and Deaths office. It shows a more recent leaning towards ‘technology-inspired’ names, such as Prepaid, Unavailable, Ringtone, and Pincode. And, while some may baulk at these names, I have come to see them as a strange but compelling living archive of history and imagination, a means to assert presence, creativity, and voice.

Cultural highlights:

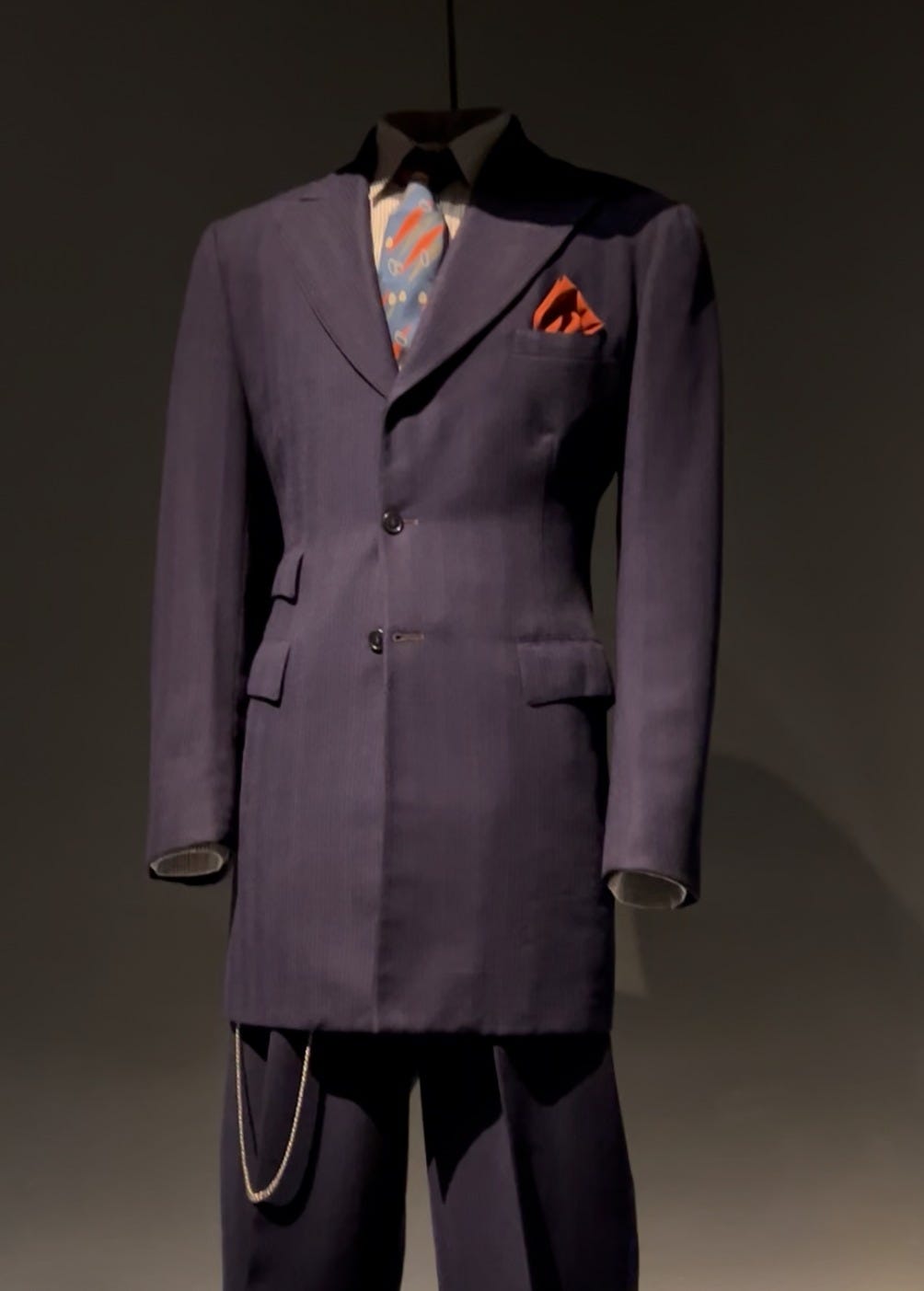

I visited the Superfine: Tailoring Black Style exhibit at the Met Museum. I have some photos up on my instagram @kimchakanetsa

Thanks for reading! Please share your thoughts on the topic of Zimbabwean names…

Really laughed at reading some of these names and loved the story behind them. As someone close to many Zimbabweans, I always found these names fascinating but as a Somali, these names remind me of some of our own traditional names for example, the name Fiidow meaning evening will be given to a child born in the ‘Evening’ and ‘Geedi or Geediyo’ will be given to a child born while the family were moving or traveling signaling the nomadic culture of the Somali people. There is also names like ‘Sheikh doon or Abti doon’ which means the mother was in labour for too long till the Sheikh or religious man came so the child was waiting for their arrival. The one good things was that Somalis never adopted any of their colonizers languages which meant, none of these were translated to English or French or Italian and they all colonized my people. Otherwise, you would’ve come across ‘strange/crazy Somali names’ on TikTok lol. Thanks for this, Kim.

Very interesting! I learnt something something new - the technology inspired names 🤣🤣🤣. Thank you for a well-researched post, Kim🙏